November 23, 2020

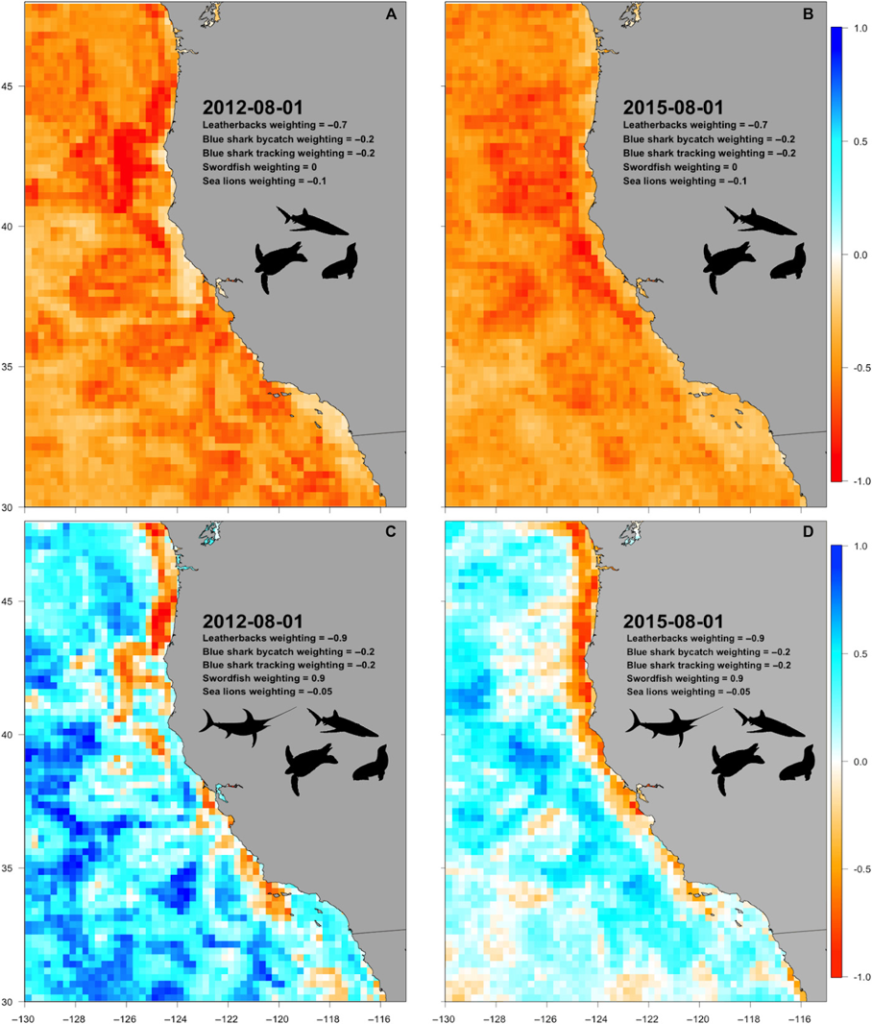

In this third installment of our ongoing series, “Forecast Spotlights”, we highlight the EcoCast nowcast and forecasts developed by Elliott Hazen, Heather Welch, and colleagues at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). EcoCast is a fisheries sustainability tool that helps fishers and managers evaluate how to allocate fishing efforts to optimize sustainable harvest of target fish while minimizing bycatch of protected or threatened animals.

The goal of the Forecast Spotlights blog series is to highlight operational forecasts being conducted by our EFI members, how they got into forecasting, and lessons learned. You can see all the ecological forecast project examples shared on the EFI Projects webpage. If you have an iterative ecological forecast project that you’d like added to this list, you can create a profile for the project using this form.

1. How did you get interested in ecological forecasting?

Elliott: A lot of my interest in ecological forecasting came from my graduate research at Duke University and learning about models forecasting seed dispersal. If such a random-seeming process such as seed dispersal could be modeled successfully it made me wonder what else could be modeled. I ended up using a lot of statistical models in my PhD to deal with the complexities of top predator datasets. In reading about these models, I realized that they could be used not just to understand ecological drivers of animal distribution but also for nowcasting and forecasting distributions moving forward. A paper by Drew Purves titled “Time to model all life on earth” also highlighted the fact that our computing capability has finally caught up to some of the questions that we have been trying to ask ecologically.

Heather: During my masters at James Cook University I worked with Bob Pressey who was concerned that our global network of MPAs (marine protected areas) was designed to protect static representations of biodiversity, despite common knowledge that many species of management concern have dynamic distributions. We started thinking about how to design management strategies to explicitly accommodate this dynamism. This was a really interesting challenge. At the time there wasn’t much in the literature about how to manage highly mobile species and so there was a lot of room for creativity. It quickly became clear that, in order to manage species that move around, we need to know where species are in real time, or better yet, ahead of time which brought me to ecological forecasting.

2. What are you trying to forecast?

We try to produce nowcasts and forecasts of the distributions of top predators and human activities to understand and mitigate their interactions, specifically interactions like fisheries bycatch and vessel collisions that put these species at risk. We, specifically Heather Welch in our group, have been predicting fishing behavior to try to identify where and why illegal fishing activities most likely to occur. The models that have predictive skill can be used to direct management and enforcement in the future.

3. Who are the potential users or stakeholders for the forecasts you create?

We target our predictions for use by fishermen and fishery managers in EcoCast, the shipping industry and protected species managers for WhaleWatch, and most recently NOAA’s Office of Law Enforcement and the US Coast Guard for Illegal, Unregulated, and Unreported forecasting efforts. We also usually hope our predictions are interesting if not useful for the broader public.

4. What are the key lessons you have learned from your forecasts?

- We often learn as much from wrong forecasts as right forecasts as it tells us where physical processes may be driving our predictions differently than expected. These outliers can be really useful to understand ecological processes and patterning.

- Engaging with stakeholders from the get-go, even before the model is built, is really important to ensure that you’re producing forecasts that are as useful as possible.

- Often maintaining and testing ongoing forecasts are as much work if not more work than building the models (Welch et al. 2018). Creating accessible tools collaboratively with stakeholders can ensure the output is as applicable as possible.

- Also, Elliott remains interested in comparing the issues and successes in terrestrial vs. marine ecological forecasting systems. While some of the questions being asked are comparable, the processes often change at different scales because of the oceanic medium compared to land and air, which keeps him wondering how the fundamental processes of forecasting may vary across these systems.

5. What was the biggest or most unexpected challenge you faced while operationalizing your forecast?

The biggest challenges in our forecasting process has largely been finding funding and ongoing support for operationalization. Specifically, funding the development of the tools have been manageable but keeping tools working and ensuring predictions remain skillful has been incredibly difficult to fund. This need for ongoing maintenance, often termed research to operations, is a fundamental gap we often face in the forecasting process.

6. Is there anything else you want to share about your forecast?

We have also been moving more and more towards public code libraries to ensure that the lessons we have learned are available to help other forecasting projects get off the ground and also to remain operational. Reproducibility in science has changed as we’ve moved more from bench and field experiments towards modeling efforts. This field, often termed “data carpentry” is going to be growing more and more in the near future to ensure that our coding efforts are done in a publicly available and reproducible manner.